My dad.

My dad died in 1974, the day after Father's Day. I miss him.

I was 23, living in Colorado and working as a carpenter, and hadn't seem him for six months. Sometimes my only live image of his face is a kind of broken television picture, black and white, full of static - like the antenna needs to be adjusted. The sound's messed up, too....I really can't remember what his voice sounded like. For all the time we spent together, I'm afraid and a little ashamed I never really got to know him very well or relate to him as an adult.

I only remember dad for what he was, and how he taught me to treat people. There are those that would have called my dad weak, somehow less a man for his poor health and poor ways, but I know that dad always tried to treat people with as much dignity and respect as he could muster. There can be no better definition of strength. In spite of a limited education, dad made friends easily, mostly because he never tried to be what he wasn't. People of every color, occupation, and social standing called my dad their friend.

Those that dared stand on the wrong side of my dad usually got what they had coming to them - in words. Dad was patently nonviolent, but could reduce anyone to rubble with a few well-chosen words. There were times when I would have preferred a good old-fashioned beating to one of his quiet verbal dismissals. Probably a good thing he wasn't a violent man, because forty years as a meat cutter left dad with strong hands that could crush you like a grape.

Dad loved the game of baseball, and would have been a big league pitcher had his father not intervened. Dad, even at his weakest, could burn a pitch into a glove, and leave you standing there, tears in your eyes, trying to shake off the pain. His motto was, "Always give them your best pitch first." He knew, and had played in semi-pro exhibition against Satchel Paige and other veterans of the Negro Leagues. Paige came over to the house several times and played catch with me. I never knew who he was until long after both he and my dad were gone. All I knew that one of my dad's friends, a long and lanky black man, could set me on my ass with a lobbed fastball.

Dad was a legend in the neighborhood. After retiring due to his health in 1962, he became a househusband, while mom continued to work for Kroger's. He cooked, cleaned, and did laundry, but never once gave the impression that life had failed him. My friends were treated as though they were part of the family. He would willingly give away anything he owned, if he thought someone else needed it, or even wanted it more than he did. In fact, dad could be categorized as a bit of a sucker, especially for the neighborhood kids. He gave away food, furniture, cars, and once, right after I first moved to Colorado, gave a young neighborhood girl, Virginia Tackett*, the huge crinkly old black Underwood office typewriter that I sort of learned to type on. When I asked him why, he replied, "She liked to type on it." (I confess I had an age-inappropriate crush on Virginia - she was five years or so younger, I was twenty, she was fifteen, and a strikingly beautiful young girl. I would have given her the typewriter myself.) The truth is, dad never valued "things" as such, and thought that anything that could make someone else happy was just begging to be given away. I suppose I have much to learn.

So it goes. Dad was famous with the girls I dated, the girls my friends dated, and anyone else who knew him. His scratch chocolate cake is still the stuff of legend, and I can thank dad's cinnamon rolls - and my sedentary ways - for my eternally pudgy waistline. More importantly, I can thank my dad for being just what he was...flawed, emotional, opinionated, generous, sometimes ignorant, hard-working, cynical, courageous and human to the core. It's quite a legacy to live up to.

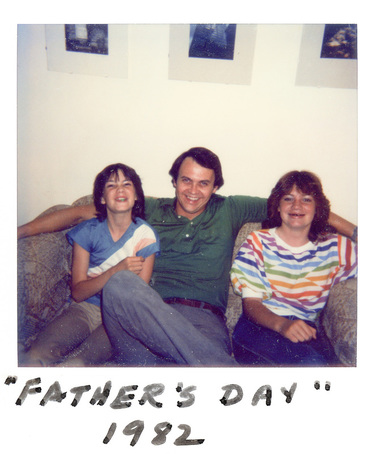

My own flaws were in full evidence with my relationship with my own girls - Kathi's daughters who I adopted immediately after Kath and I married in 1983. But the lessons I learned from my own dad were always in evidence. For better or worse, I gave it my best pitch.

My dad died in 1974, the day after Father's Day. I miss him.

I was 23, living in Colorado and working as a carpenter, and hadn't seem him for six months. Sometimes my only live image of his face is a kind of broken television picture, black and white, full of static - like the antenna needs to be adjusted. The sound's messed up, too....I really can't remember what his voice sounded like. For all the time we spent together, I'm afraid and a little ashamed I never really got to know him very well or relate to him as an adult.

I only remember dad for what he was, and how he taught me to treat people. There are those that would have called my dad weak, somehow less a man for his poor health and poor ways, but I know that dad always tried to treat people with as much dignity and respect as he could muster. There can be no better definition of strength. In spite of a limited education, dad made friends easily, mostly because he never tried to be what he wasn't. People of every color, occupation, and social standing called my dad their friend.

Those that dared stand on the wrong side of my dad usually got what they had coming to them - in words. Dad was patently nonviolent, but could reduce anyone to rubble with a few well-chosen words. There were times when I would have preferred a good old-fashioned beating to one of his quiet verbal dismissals. Probably a good thing he wasn't a violent man, because forty years as a meat cutter left dad with strong hands that could crush you like a grape.

Dad loved the game of baseball, and would have been a big league pitcher had his father not intervened. Dad, even at his weakest, could burn a pitch into a glove, and leave you standing there, tears in your eyes, trying to shake off the pain. His motto was, "Always give them your best pitch first." He knew, and had played in semi-pro exhibition against Satchel Paige and other veterans of the Negro Leagues. Paige came over to the house several times and played catch with me. I never knew who he was until long after both he and my dad were gone. All I knew that one of my dad's friends, a long and lanky black man, could set me on my ass with a lobbed fastball.

Dad was a legend in the neighborhood. After retiring due to his health in 1962, he became a househusband, while mom continued to work for Kroger's. He cooked, cleaned, and did laundry, but never once gave the impression that life had failed him. My friends were treated as though they were part of the family. He would willingly give away anything he owned, if he thought someone else needed it, or even wanted it more than he did. In fact, dad could be categorized as a bit of a sucker, especially for the neighborhood kids. He gave away food, furniture, cars, and once, right after I first moved to Colorado, gave a young neighborhood girl, Virginia Tackett*, the huge crinkly old black Underwood office typewriter that I sort of learned to type on. When I asked him why, he replied, "She liked to type on it." (I confess I had an age-inappropriate crush on Virginia - she was five years or so younger, I was twenty, she was fifteen, and a strikingly beautiful young girl. I would have given her the typewriter myself.) The truth is, dad never valued "things" as such, and thought that anything that could make someone else happy was just begging to be given away. I suppose I have much to learn.

So it goes. Dad was famous with the girls I dated, the girls my friends dated, and anyone else who knew him. His scratch chocolate cake is still the stuff of legend, and I can thank dad's cinnamon rolls - and my sedentary ways - for my eternally pudgy waistline. More importantly, I can thank my dad for being just what he was...flawed, emotional, opinionated, generous, sometimes ignorant, hard-working, cynical, courageous and human to the core. It's quite a legacy to live up to.

My own flaws were in full evidence with my relationship with my own girls - Kathi's daughters who I adopted immediately after Kath and I married in 1983. But the lessons I learned from my own dad were always in evidence. For better or worse, I gave it my best pitch.