Back in the middle sixties, after a run of really bad cars - the ’47 Chevy Stylemaster I remember as the first car I ever rode in; a green '51 Plymouth four-door, a peach-colored '54 Plymouth Belvedere, an unsuccessful two-day stab at owning a '50 Buick Coupe*, and in a effort to make my mother's daily commute to 31st and Minnesota Avenue a bit nicer, dad went downtown to Greenlease Cadillac and picked out a baby blue '55 four door Cadillac Series 62 sedan.

Knowing my dad, I'm sure he paid more for it than it was worth - a family trait, I've discovered - but what a car! It had a 331 inch V-8 and a four barrel carb, useful in producing the necessary horsepower to motivate this eleven-ton monstrosity down the road.

Knowing my dad, I'm sure he paid more for it than it was worth - a family trait, I've discovered - but what a car! It had a 331 inch V-8 and a four barrel carb, useful in producing the necessary horsepower to motivate this eleven-ton monstrosity down the road.

Post-war optimism at it's most vulgar, the Cadillacs of the Fifties were big gas-guzzling rolling monuments to American consumerism, jet-age design, and wretched excess. Oh, and sex. Cadillacs had these gigantic, heavy metal chrome boobs sticking out the front of the bumper. They were known as “Dagmars". The egg crate grill seemed ready and able to eat anything that dared venture close enough to be lured into its gaping chrome maw. It was a mid-century miracle on wheels.

What my father failed to realize was that you didn't just buy a Cadillac, you entered into a long-term relationship with the dealer and a team of full-time mechanics that existed only to rid you of your hard-earned cash. The Cadillac 331 cubic inch V-8 was a mechanic's dream and an owner's nightmare - plus, years before the concept became popular, parts for a Cadillac were twice the price of an equivalent part for, say, a Chevrolet or Ford. Hell, just the tires were an investment. You didn't go to Western Auto for plain old garden variety Wizard bias ply tires when the car you're putting them on weighed as much as an armored car. General Dual 90s were the tires of choice for Cadillacs.

What my father failed to realize was that you didn't just buy a Cadillac, you entered into a long-term relationship with the dealer and a team of full-time mechanics that existed only to rid you of your hard-earned cash. The Cadillac 331 cubic inch V-8 was a mechanic's dream and an owner's nightmare - plus, years before the concept became popular, parts for a Cadillac were twice the price of an equivalent part for, say, a Chevrolet or Ford. Hell, just the tires were an investment. You didn't go to Western Auto for plain old garden variety Wizard bias ply tires when the car you're putting them on weighed as much as an armored car. General Dual 90s were the tires of choice for Cadillacs.

I have to admit, trips to Fort Scott to see my grandmother were far less torturous in a Cadillac than they were in any of our other cars. At least the road seemed smoother in a Cadillac. The trip that seemed like eight hours in a Plymouth, all but floated by in the Cadillac. The FortScott Tribune probably ran a one-inch filler in the “Comings and Goings” section about the Simpsons from Kansas City coming to visit in their shiny new car.

For me, the Cadillac became something of a hobby - my dad would go fishing at an area pay lake, and I'd tag along and give the blue monster a fresh coat of Genuine Blue Coral Paste Wax while dad tried to convince carp that he knew what was best for them. For me, anything was better than fishing. I nagged dad to let me drive in exchange for my cramped and sore waxing muscles, but no deal. One Sunday in October my mom was feeling a bit blue. She was facing a union lockout at work, and wasn’t at all sure how we were going to make ends meet. There was no way she was going to be able to sit next to a lake with dad. So she dropped dad and his fishing tackle off at the 40 Hiway Club Lake, and she and I headed toward Leavenworth and the Family Plot, our little Bethel Cemetery, to visit her dad’s grave. After an appropriate period of cemetery solemnity followed by endless only-child wheedling and whining, she tossed me the keys. I got my first shot at driving that monster Caddy over highway 92 west of Leavenworth, through Oskaloosa, and eventually, on to Topeka. Mind you, I'm thirteen, unlicensed, and more than a little bit scared, but mom had confidence in me, and I had been waiting for this opportunity since I knew what a car was. The sky was a deeper blue than usual, the sun was shining only on me. The thrill of mashing the big pedal and feeling that Cad hunker down and flatten the hills of northeast Kansas gave me my first real taste of unbridled internal combustion lust. I have yet to fully recover my senses. Mom may have actually thrown up when we got to Topeka. Maybe not.

The Cadillac, chauffeured by my dad, got me and my date to a senior class production of The Pajama Game at Northeast High School when I was thirteen. That date was followed by hot-fudge sundaes at Allen’s Dairy on Independence Avenue. It wasn’t the St. James Theatre, and I was so nervous I could barely speak to my date (Hi, Patty!), but I felt like I had won the lottery. There were a couple more evenings like that before I was able to drive on my own - a huge back seat in a massive luxury car, piloted by a dad who became instantly and uncharacteristically, invisible. Patty and I were in Hernandos' Hideaway, all alone. I get goosebumps just thinking about it.

Dad saw 5,000 lbs of Detroit Iron as having tremendous potential. As a truck. He had started manufacturing carp and catfish baits in the early ‘50s, and when we moved to Kansas City in 1955, he and my uncle Lawrence dug out a basement under the little rental house to serve as his production facility. If you don’t think my mom was a saint, think again.

The trunk of that car would hold three big bags of wheat shorts or unbleached flour, untold number of paper cans and liners, and the happiest discovery of my dad’s life, a 55 gallon barrel. He developed a method for getting a fully loaded barrel of blackstrap molasses out of the back of the car, and down into the basement bait factory without scratching the Cadillac’s bumper. Barrels of cheese scraps made the same journey, as did 425 loaves at a time of day-old white Tastee Bread. I told you my mom was a saint.

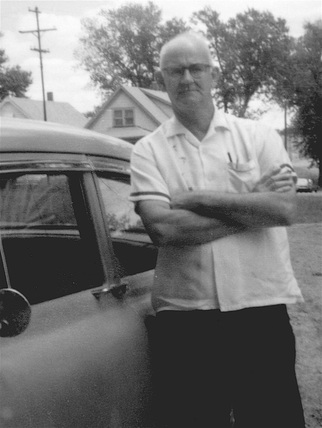

My dad never had much in his life in the way of material possessions, and looking back, the '55, with its fins and nacelles, its scoops and chrome, was probably a lot more than my dad needed or my mom wanted, but somehow it seems right that dad got one thing that made him feel head and shoulders above the rest of the world. he had, in his now way, earned it.

I never really had the privilege of asking dad for the keys to the '55, because by the time I was old enough, I had already rounded up my own wheels, and the stodgy, patina-covered Cadillac didn't have much appeal for me then.

As age took its toll on the Cadillac, and the team of mechanics assigned to the monster car spent more time under the hood, dad grudgingly sold it to one of my friends for fifty bucks and bought my mom a ’69 Ford Galaxie. I complained. Not only was it not a Cadillac, it was horribly misspelled. It was the last car dad would ever drive. Every Sunday, when he and mom would call me in Colorado to check in, he’d ask,

“What kind of car are you driving?”

“Chevy truck, dad. It drives like a Cadillac.”

“That’s good.”

For me, the Cadillac became something of a hobby - my dad would go fishing at an area pay lake, and I'd tag along and give the blue monster a fresh coat of Genuine Blue Coral Paste Wax while dad tried to convince carp that he knew what was best for them. For me, anything was better than fishing. I nagged dad to let me drive in exchange for my cramped and sore waxing muscles, but no deal. One Sunday in October my mom was feeling a bit blue. She was facing a union lockout at work, and wasn’t at all sure how we were going to make ends meet. There was no way she was going to be able to sit next to a lake with dad. So she dropped dad and his fishing tackle off at the 40 Hiway Club Lake, and she and I headed toward Leavenworth and the Family Plot, our little Bethel Cemetery, to visit her dad’s grave. After an appropriate period of cemetery solemnity followed by endless only-child wheedling and whining, she tossed me the keys. I got my first shot at driving that monster Caddy over highway 92 west of Leavenworth, through Oskaloosa, and eventually, on to Topeka. Mind you, I'm thirteen, unlicensed, and more than a little bit scared, but mom had confidence in me, and I had been waiting for this opportunity since I knew what a car was. The sky was a deeper blue than usual, the sun was shining only on me. The thrill of mashing the big pedal and feeling that Cad hunker down and flatten the hills of northeast Kansas gave me my first real taste of unbridled internal combustion lust. I have yet to fully recover my senses. Mom may have actually thrown up when we got to Topeka. Maybe not.

The Cadillac, chauffeured by my dad, got me and my date to a senior class production of The Pajama Game at Northeast High School when I was thirteen. That date was followed by hot-fudge sundaes at Allen’s Dairy on Independence Avenue. It wasn’t the St. James Theatre, and I was so nervous I could barely speak to my date (Hi, Patty!), but I felt like I had won the lottery. There were a couple more evenings like that before I was able to drive on my own - a huge back seat in a massive luxury car, piloted by a dad who became instantly and uncharacteristically, invisible. Patty and I were in Hernandos' Hideaway, all alone. I get goosebumps just thinking about it.

Dad saw 5,000 lbs of Detroit Iron as having tremendous potential. As a truck. He had started manufacturing carp and catfish baits in the early ‘50s, and when we moved to Kansas City in 1955, he and my uncle Lawrence dug out a basement under the little rental house to serve as his production facility. If you don’t think my mom was a saint, think again.

The trunk of that car would hold three big bags of wheat shorts or unbleached flour, untold number of paper cans and liners, and the happiest discovery of my dad’s life, a 55 gallon barrel. He developed a method for getting a fully loaded barrel of blackstrap molasses out of the back of the car, and down into the basement bait factory without scratching the Cadillac’s bumper. Barrels of cheese scraps made the same journey, as did 425 loaves at a time of day-old white Tastee Bread. I told you my mom was a saint.

My dad never had much in his life in the way of material possessions, and looking back, the '55, with its fins and nacelles, its scoops and chrome, was probably a lot more than my dad needed or my mom wanted, but somehow it seems right that dad got one thing that made him feel head and shoulders above the rest of the world. he had, in his now way, earned it.

I never really had the privilege of asking dad for the keys to the '55, because by the time I was old enough, I had already rounded up my own wheels, and the stodgy, patina-covered Cadillac didn't have much appeal for me then.

As age took its toll on the Cadillac, and the team of mechanics assigned to the monster car spent more time under the hood, dad grudgingly sold it to one of my friends for fifty bucks and bought my mom a ’69 Ford Galaxie. I complained. Not only was it not a Cadillac, it was horribly misspelled. It was the last car dad would ever drive. Every Sunday, when he and mom would call me in Colorado to check in, he’d ask,

“What kind of car are you driving?”

“Chevy truck, dad. It drives like a Cadillac.”

“That’s good.”

On a sultry, early-summer day in 1974, six men wearing black suits and Masonic aprons loaded my dad's casket into a hearse for the trip to his gravesite in our Leavenworth County cemetery. I cried because I had lost my father, but I laughed because his last ride was a sleek, black Cadillac.

*The Buick was just about the coolest car my dad ever tried to own - he bought it at Jack's Used Cars at Eighteenth and Garfield in Kansas City, Kansas - "Make Tracks to Jack's and Ride Back". Black over white two-tone, menacing overbite grill, two doors instead of the more practical four, and the signature radio antenna right smack above the center of the swoopy wrap-around windshield made the Buick a rolling sex machine. It had monstrous straight-eight power, and the air conditioner was so cold you could hang beef in the back seat. And portholes, I almost forgot the Harley Earl portholes. "Ventiports" if you want to be accurate. Dad, though, was miffed about some perceived car-dealer injustice, and took the Buick back after two days, by God. What a shame.